Audubon’s Western Yellow-billed Cuckoo (YBCU) biologists began the 2021 survey season in drought-stricken waterways and ended them in humid, insect-rich streams that were barely recognizable. How does the whiplash from baking dryness to lush but late green-up impact nesting birds? Consider that YBCU are late arrivals in southwestern riparian areas, their migration timed to a predictable monsoon season. Cuckoos rely on the insect cornucopia that explodes with mid-summer rains and this bounty fuels the rapid growth of nestlings that are amazingly fully feathered within 10 days of hatch. Our crew has witnessed the ravages of drought and the increasingly unpredictable monsoon schedule for 10 years. We’re considering adding a crystal ball to the gear box!

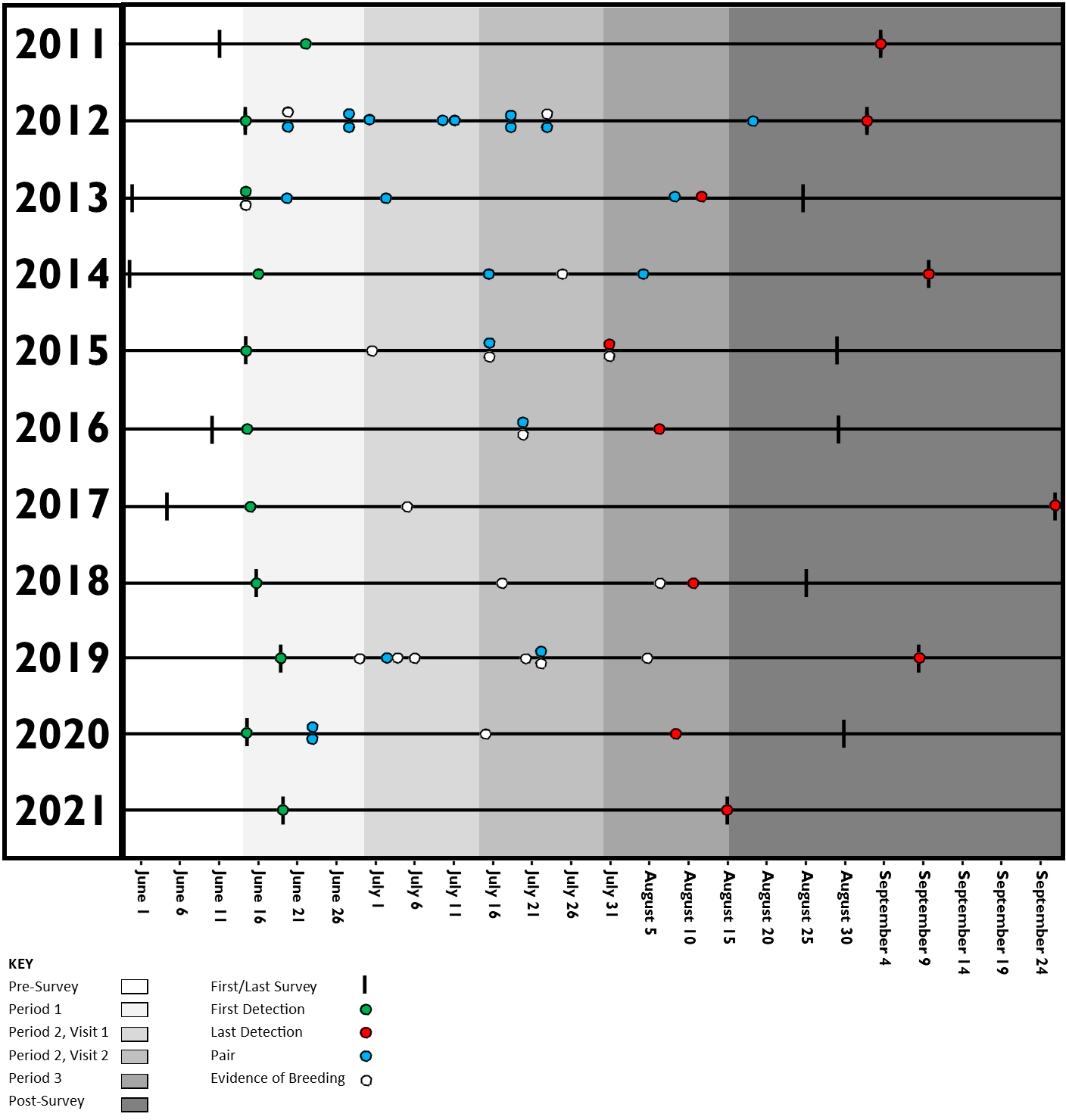

This year, Arizona’s Audubon Southwest team and collaborators from three Audubon chapters (Sonoran, Prescott, and Sun Devil) surveyed 13 routes across 3 watersheds (Upper Verde, Salt, Agua Fria) and including 2 IBAs (Upper Verde State Wildlife Area, Agua Fria National Monument). All told, surveyors made 163 individual cuckoo detections representing 30 potential breeding territories. While cuckoo numbers were comparable to previous years, timing was skewed – something to keep an eye on. It is likely that cuckoos pushed their breeding back in accordance with insect productivity. The busy graph below summarizes data from our Agua Fria National Monument survey detections over time. Note that this year, we did not report pairs or suspected breeding activity. The only other year in which this was true was 2011, and that was likely due to lighter survey effort.

Our limited data suggest that in 2021, birds reacted early in the season by selecting the best habitat available despite dry conditions. Birds seemed to avoid areas damaged by human impact and to favor areas with residual surface water or wet soil. Cuckoos called for mates in these areas as they would in “typical” years, and then became quiet. Once the rains hit, humidity increased later than usual as did cuckoo activity, but the survey season ended with questions remaining. Did cuckoos nest successfully by hanging around later to do it? How will this timing shift effect their migration south and their fitness once on the wintering grounds? Both cuckoos and humans would do well to be concerned about the future, but hopeful.

Why hopeful? The 2021 Yellow-billed Cuckoo (YBCU) survey season marked the first time National Audubon’s Western Water Network Grants enabled a central Arizona Audubon chapter to recruit and hire YBCU surveying interns. Sonoran Audubon brought on three Arizona State University students, Mikaea Joerz, Emily Thomas, and Dalton Sonnenberg, along with one graduate, Kaylee Delcid, to assist experienced volunteers in monitoring efforts on the Agua Fria National Monument. The enriched team contributed to a more robust field effort and the promise of a “pass the torch” approach to replacing experienced surveyors as they move on to other adventures. Note that Audubon efforts over the last 10 years resulted in the inclusion of key drainages in Agua Fria National Monument in the USFWS Critical Habitat designation for YBCU in 2021. The addition of new volunteers to the effort signals that the cuckoo surveys are sustainable and we can continue to assess climate change impacts as time passes. Now that we can no longer ignore or deny the reality of climate change, community members and politicians alike are rolling up their sleeves to make a difference for wildlife and that’s hopeful, too.

Resiliency is a word thrown around a lot lately, and in the natural world, it is better spelled “complexity”. The seasonal interplay of daylight length (it hasn’t changed) with plant growth and insect productivity (which is changing markedly and erratically) has unpredictable outcomes for birds and the planet. Science provides models, but animal behavior related to these changes is inscrutable. For now.