By Tom Taylor, Resident Birder, Santa Fe, NM

In the next few weeks, this column will take you on a cyber-tour around the country during the spring songbird migration. This is the second column during the COVID-19 pandemic confinement. The tour begins in the southwestern part of the US, where the author resides in Santa Fe, NM. For more than ten years each spring he has taken at least one photographic outing to another part of the country to follow the arrival of the neo-tropical migrants from Central and South America. The reader can link to other articles in the series using the references at the bottom of this page.

To begin again, there are obvious behavioral changes in our year-round local bird species as they gear up for the nesting season. Always the "early bird”, the Curve-bill Thrashers in my neighborhood are already incubating eggs in a nest that has once again been built in a nearby cholla cactus. The top photo shows a thrasher perched in a cholla near a nest site from a previous year. Once the fledglings appear, they go through a comical crash test on how to use my suet feeder. The trick for them being that, unlike woodpecker species, they do not know how to use their tail feathers—retrices—for support on the tailpiece.

One of the earliest spring signs is bird vocalization. The House Finches are now in a strong chorus and, occasion, there is a glorious solo from a Bewick’s Wren as it sings to attract a mate. Like all wrens they have a feisty manner, are quite active, and can scold while habitually flicking their tails. Notice the prominent white eyebrow—supercilium—in the photo of the Bewick’s Wren that helps distinguish it from a House Wren, also found in this area.

One of the earliest flashes of color, apart from the hummingbirds, could well be the intense yellow of male Lesser Goldfinches, which have started to appear on my Nyjer Seed sock. These birds are not entirely absent in the winter, but they are now starting to colorfully make a larger appearance.

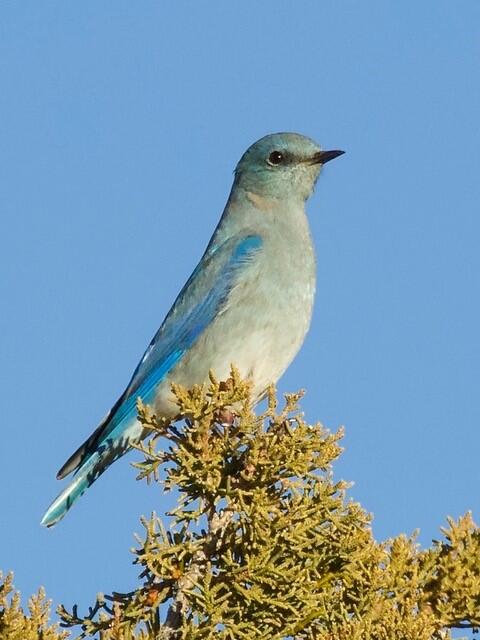

In a different vein, I am regularly taking hikes in the open fields and residential space south and west of town using strict adherence to social distancing. At this time the most colorful bird sightings, apart from the multitude of House Finches, are the Western and Mountain Bluebirds that can be easily photographed atop the Pinyon and Juniper trees. Both the bluebird photos show males, which give the most striking blue hues when compared to the females. There is a very important connection in both the photos as it pertains to the blue color of the birds and the background sky.

A sometimes under-appreciated fact is that birds (except in very rare instances) have no blue pigment in their feathers. Their color, as is the case for these bluebirds, is due to the scattering of light from the feather surfaces by very small (nanometer dimension) air vacuoles, that preferentially redirects the blue (short) wavelengths of light while the longer wavelengths are absorbed by the feathers. Analogously, the blue sky results from the same sort of mechanism, where the short (bluish) wavelengths get strongly scattered by air molecules. They are redistributed in space and illuminate the upper atmosphere. At sunset, when the glancing atmospheric pathway is at its most extreme, the remaining red-shifted portion of the spectrum creates the golden-red color schemes.

You might easily imagine that in normal birding times I would spend precious little time walking through these brushy open fields. True, and I would belittle any chances of getting a high-quality bird photograph. But, in birding, there are always surprises. The Horned Lark photo is quite easily the best that I have ever taken as they are almost always hidden in the groundcover. Thanks to a couple excavation mounds in this area, this bird was clearly perched in the open – and showing a quite nice yellow/black head pattern. Note the slight suggestion of the horns atop the head.

Here is a sure indication of spring. The Say’s Phoebe, with that striking black tail, is a flycatcher that is very common here in the summer. They often nest in the portals around town and are usually quite unaffected by our activities.

Lastly, the Chipping Sparrow is the first that I have seen this year. It is undoubtedly the first trickle of the wave of migrants to appear here. This being the middle of April, there have been a number of eBird rare-bird reports showing the early arrival of the summer songbirds. The ones meriting the rare-bird alert category are often the summer warblers, which have begun to show up from south of the US. In a couple weeks we will begin to see Western Tanagers.

In lieu of waiting their arrival, the next column will start the first leg of a virtual trip to the north Texas coast, where we will experience the arrival of the eastern songbirds after they have flown across the Gulf of Mexico from the Yucatan.